Exercise Programming for Clients Who Have Arthritis

An estimated 60 million Americans are living with some form of arthritis, according to data from the Arthritis Foundation. That’s one in five people, which could include one or more of your clients. Unfortunately, the pain of arthritis leads many individuals to abandon their physical activity efforts, which increases their risk of obesity and other chronic conditions that can further increase their pain and risk of disability.

The two most prevalent forms of arthritis are osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Both conditions are characterized by irreversible damage within synovial joints, which leads to pain, swelling, stiffness and movement limitations. Because there is no known cure for either of these forms of arthritis, they ultimately progress toward long-term disability. In fact, arthritis is the number-one cause of disability among adults in the United States.

Common Myths About Arthritis

A myth can be defined as an untrue explanation for a natural phenomenon. Unfortunately, numerous myths remain pervasive and deeply engrained in the health and fitness world. In this section, we take a look at several common myths surrounding arthritis.

- Arthritis is an inevitable part of aging. For this myth to be true, most adults and no children would have arthritis. Yet, more than half of older adults never experience arthritis, and nearly 300,000 children do experience juvenile arthritis.

- Rest is best. A common misunderstanding is that exercise is not feasible in the management and treatment of arthritis. This myth can lead to inactivity and sedentary lifestyles, which we know as health and exercise professionals leads to heighted risk of disability and other chronic diseases. Research has made it abundantly clear that individualized exercise is beneficial and safe for clients with arthritis.

- Some arthritic joints are beyond repair and there is no cure. Many clients unnecessarily feel their arthritis is too far advanced to be treated. However, research has shown that appropriate management can help alleviate pain and other symptoms of arthritis. Exercise and rehabilitation, medication, education and surgery are all effective for this limiting condition.

For these reasons, it is critical that you understand the unique needs of this vulnerable population. In this article, we share lessons gleaned from years of experience working with individuals who have arthritis and offer guidance on how you can develop safe and effective exercise programs for your clients who may be dealing with this health challenge.

The Pathophysiology of OA and RA

Understanding the underlying mechanisms of OA and RA can help you develop more individualized and appropriate programs. Here are brief descriptions of each:

Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA is a degenerative joint disease that is characterized by local degeneration of the articular cartilage, accompanied by new bone synthesis at the joint margins and thickening of the synovial capsule. The most commonly affected joints are the knees, hips, spine, hands and feet. Risk factors for the development and progression of OA include age, sex (female), ethnicity, obesity, muscle weakness, mechanical forces, occupation (e.g., jobs that are more likely to be associated with overuse and repetitive trauma) and a history of past injury.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease that affects the synovial cavities of synovial joints. It occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the joint tissues, leading to synovitis. During active periods of inflammatory synovitis, a person with RA will experience warm, red and swollen joints, with the hands, wrists, feet, ankles, elbows, shoulders, knees, hips and cervical spine most commonly affected. Risk factors for RA include family history, obesity and smoking. Because it is an autoimmune disease, RA often strikes younger people, is not associated with past injuries, and can affect all the joints in the body, often with a cumulative effect. Due to chronic inflammation, individuals with RA are twice as likely to have accelerated atherosclerosis as compared to the general population, which puts them at greater risk of heart attack and stroke.

Conditions Often Associated With Arthritis

Individuals who have arthritis often have other chronic conditions as well. The prevalence of arthritis is most frequent among adults with the following chronic conditions:

- Heart disease (49.0%)

- Type 2 diabetes (47.0%)

- Obesity (28.8%)

Exercise is relatively safe for most clients who have chronic health concerns provided that appropriate assessment and screening is performed prior to beginning the program. The likelihood of an adverse event, although not entirely preventable, can be significantly reduced with baseline assessments, education and client adherence to established exercise recommendations. Always take the time to check in with your client’s medical team about any specific limitations to be aware of when designing the exercise program.

Common Medication–Exercise Response Considerations

The medical management of arthritis may include a broad range of medications. As mentioned in the previous section, clients who have arthritis often have comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease, so it is critical that you understand the interaction of certain medications with the exercise response and how the exercise program might need to be adjusted. For example, common medications prescribed to Americans include beta blockers for heart disease and oral hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetes. Beta blockers elicit lower heart-rate and blood-pressure responses to a given exercise workload, and for individuals taking oral hypoglycemics, the combination of exercise and medication can result in hypoglycemia (or low blood sugar levels). The most important program modification for clients taking oral hypoglycemics is frequent monitoring of blood sugar values.

Clients who have arthritis are also likely to be taking analgesics (painkillers) and anti-inflammatory medications to manage pain and other symptoms of the disease. In fact, approximately 85% of individuals with OA have received a prescription for their pain, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) being the most common. Another study reported that two out of three individuals with RA used pain medications. Although it is advisable to urge clients to exercise at the time of day when the effectiveness of their pain medications is at its highest, it is worth noting that exercise under the influence of analgesic medications may impair muscle adaptation. As such, we likely need to temper the client’s expected training outcomes.

The intent of this section is not to be exhaustive in its scope, but rather to underscore the importance of being aware that medications can affect a client’s response to exercise and should be considered when designing their program. It’s also critical to collaborate with the multidisciplinary team of medical providers who manage your client’s arthritis and familiarize yourself with other relevant medications and considerations for overall exercise programming.

Three Rules of Program Design for Clients Who Have Arthritis

Three basic rules should guide your program design for clients who have arthritis:

- Regularly incorporate range-of-motion activities.

- Progress slowly.

- Build trust.

Increasing range of motion (ROM) and decreasing stiffness are important initial programming goals. Decreased stiffness results in better posture and improved movement patterns, which lessens the chance for further injury and/or falls. It may also be helpful to show your clients research that regular activity/exercise reduces pain, as they might not believe you, as some people with arthritis are erroneously told that the opposite is true (i.e., rest is best).

Alert your clients to the fact that, at least for the first several weeks of a new program, they will likely experience more pain, stiffness and swelling when incorporating new ROM activities. For this reason, progressing slowly is essential. Many symptoms will not show up for one to two days afterward and doing too much too quickly is a recipe for failure, especially if your client doesn’t know what to expect. However, if you explain to your client that their symptoms might actually get worse at the beginning of their program, but reassure them that they will get better by the third week or so, their trust in you will increase and they will be more likely to stick with their program.

It's also important to urge clients to stop doing any activity that seems to irritate or cause pain in a specific joint. While reducing the ROM of an activity may help a client avoid pain, this is not an ideal approach. Alternatively, aim to identify a different activity for your client that works the same muscle group, but does not cause pain. Be creative and employ some purposeful trial and error to get it right.

Overall, we find it beneficial to have clients take each joint or the affected joints through their full ROM unloaded prior to exercise; these movements should also be practiced on the days when they are not exercising with you. It only takes a few days of inactivity for stiffness to start coming back, so clients who have arthritis really need to be consistent with their exercise program. This will help them avoid a cycle of joint stiffness when stopping activity and then new soreness/stiffness when they start back up again.

Focus on Functional Exercises

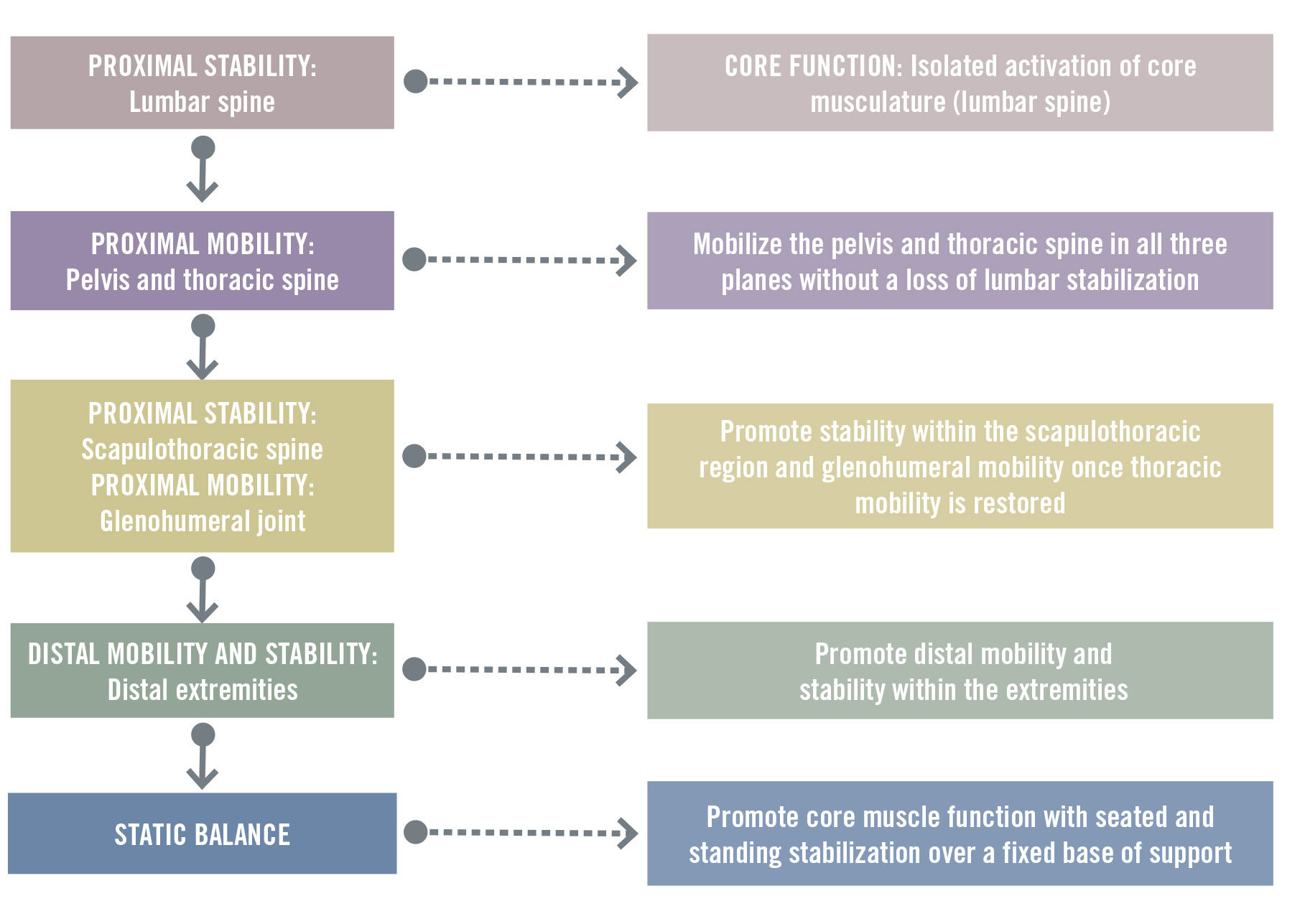

For many clients who have arthritis, starting with functional exercises is recommended because pain and immobility can lead to muscular atrophy and imbalance. The objective of functional movement training is to reestablish appropriate levels of stability and mobility within the body. This process begins by targeting the lumbar spine, which encompasses the body’s center of mass, and the core. As this region is primarily stable, programming should first promote stability of the lumbar region through the action and function of the core musculature. Once an individual demonstrates the ability to stabilize this region, you can progress their program to include more distal segments.

Adjacent to the lumbar spine are the hips and thoracic spine, both of which are primarily mobile. As thoracic spine mobility is restored, you can adjust a client’s program to target stability of the scapulothoracic region. Finally, once stability and mobility of the lumbo-pelvic, thoracic and shoulder regions have been established, you can shift their program to enhancing mobility and stability of the distal extremities. Attempting to improve mobility within distal joints without first developing more proximal stability only serves to compromise any existing stability within these segments. When a joint lacks stability, many of the muscles that normally mobilize that joint may need to alter their true functions to assist in providing stability. Figure 1 illustrates a programming sequence for promoting stability and mobility within the body. It adheres to the basic principle that proximal stability facilitates distal mobility.

Figure 1. Programming Considerations for Functional Training

Table 1 presents a menu of stability and mobility exercises to help you plan and implement programs for your clients. You may opt to select from this list or use other exercises that are individualized to a client’s specific needs and areas that require attention. Once a client demonstrates improvements in stability and mobility, they can progress from the Functional Training phase to the Movement Training phase of the Muscular Training component of the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model (more on this below).

Table 1. Stability and Mobility Exercises

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow the ACE IFT Model Guidelines With Special Considerations

In general, you can use the ACE IFT Model guidelines to create individualized cardiorespiratory and muscular training program for clients with arthritis. However, keep these special programming considerations in mind:

- For cardiorespiratory training, prioritize increasing exercise duration vs. intensity.

- For muscular training, prioritize lighter resistance and more repetitions.

- Limit or avoid exercise during periods of acute flare-ups and inflammation. Clients will feel achy in their joints and will likely be experiencing fatigue. Their pain level will be two to three points higher on the pain scale than their “normal” level. Even ROM activities should be discontinued at this time.

- Stop the exercise session if your client experiences joint pain that is too severe to continue. We recommend a threshold of 4 on the RPE discomfort scale.

- An appropriate warm-up and cool-down of five to 10 minutes each can help to lessen pain. The warm-up should include ROM activities, while the cool-down should include static stretching.

- Suitable footwear that provides cushioning and stability are especially important for clients who have OA.

- Aquatic exercise in warm water (i.e., 83 to 90° F; 28 to 32° C) is an excellent option given its muscle-relaxing and analgesic properties.

- Arthritis is common in older adults, so be sure to follow comprehensive exercise programming guidelines for these clients.

Flexibility exercises are highly beneficial for clients who have arthritis and should be emphasized. Because muscles contribute to movement in all three planes, be sure to incorporate flexibility exercises that lengthen the muscles in all three planes. It is important, however, to focus on the muscle’s primary plane of movement before adding complexity by introducing movement in other planes. For example, when stretching the hip flexors using a half-kneeling lunge stretch, instruct the client to stretch the muscle in the sagittal plane before incorporating any frontal or transverse plane movements into the stretch (e.g., a lateral trunk lean or trunk rotation).

The general FITT approach to exercise programming (i.e., frequency, intensity, time and type) used for cardiorespiratory and muscular training program design can also be applied to flexibility exercise programming. Ideally, flexibility training should be performed daily, if possible, for approximately 10 minutes per session.

Summary

Working with clients who have specific health challenges such as arthritis can be highly rewarding. Regular exercise has been shown to slow the progression of arthritis, help manage its symptoms and improve overall quality of life. To learn more about this disease and how to work with individuals who have arthritis, please check out these resources:

Expand Your Knowledge

Moving With Arthritis

In this video training, Dianne McCaughey, Ph.D.—a gerontology expert, international speaker and author—shares two perspectives of arthritis: the client and the exercise professional. Having experienced life-long joint pain, McCaughey brings first-hand knowledge of the psychological effects of arthritis as well as expertise on designing exercise programs to keep clients moving. You will learn a variety of methods to use while training individuals with arthritis so they can feel empowered to complete their daily routines and partake in activities they enjoy.

Training Active Agers With Osteoarthritis

In this course led by Tanya Thompson, founder and owner of Pilates Unlimited–The Art of Movement™, you will learn the fundamentals of training older adults and how to help them continue exercising safely through a focused osteoarthritic program. You will discover modifications and assists that will make your program safe and effective—and will encourage joint care and longevity for your clients who have osteoarthritis.

Program Design for Clients With Osteoarthritis

In this video training, you’ll learn how to develop safe and effective exercise programs for clients who have osteoarthritis or are at risk of developing it. You’ll also receive guidance on gathering important client information, helping set realistic client expectations, designing appropriate gym and home exercise programs, addressing pain management and communicating with sensitivity. You will walk away feeling empowered to inspire your clients to be physically active so they may have improved pain, mobility and quality of life.